By Liam O’Farrell

Participatory planning

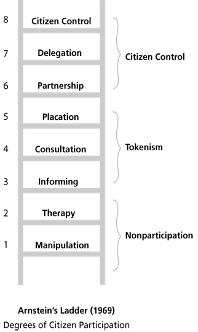

Participatory planning is about empowering citizens to make decisions that shape the physical world they live in. Participatory planning theory draws from Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation (see diagram to the left, taken from the Citizen’s Handbook). Although there have been many revisions to the ladder model since it first appeared in 1969, Arnstein set the standard for how participatory urban planning, and civic engagement more generally, is conceptualised.

The Ladder of Participation is a mechanism for rethinking dominant knowledge and power hierarchies. In participatory planning, communities are empowered to diagnose their own problems and formulate solutions or visions for the future that are rooted in their lived experience. While technical experts can be involved as facilitators or to provide information, ideally citizens should shape the process themselves as far as possible.

Current models of public consultation in urban planning have the effect of shutting some people out of the planning process or restricting the range of choices available. Allowing communities to have a greater degree of control over their areas and set their own priorities increases engagement, and in doing so increases trust in planning and politics. It also builds consensus for developments, particularly when these are controversial and residents perceive that the changes are being ‘done to them’ by the local authority, rather than being done ‘with them’, ‘for them’ or ‘by them’.Participatory planning is a means of ensuring that the views of the most marginalised groups are factored into the decision-making process. Such inclusion creates a sense of ownership and motivation diffused throughout the community, promoting positive change that is highly context specific. As with other methods of civic engagement, the idea is that the products of such a process are more holistic and reflective of the challenge they seek

Following a major earthquake in 2011 that destroyed much of the city, Christchurch City Council developed the Resilient Greater Christchurch Plan to rebuild in a participatory manner. The plan sought to incorporate principles of resilience into urban planning. This includes preparedness for natural disasters and climate change and also tackling the causes of social instability, such as long-term unemployment, poor public transport infrastructure, and inclusion of marginalised groups.

The initial scope of the plan was drafted by the local authority in collaboration with stakeholder groups, with an unprecedented level of public engagement that generated 106,000 ideas over 6 weeks of consultation. These were fed into the development of the plan. However, the final iteration of the plan prioritised technical expertise over the lived experience and subjective knowledge of citizens. This demonstrates how the belief persists that technical knowledge of experts is objective, true, and sufficient, whereas local knowledge is considered subjective or irrelevant. Studies have shown that the opposite can in fact be true, with technical knowledge being based on uncertain or problematic assumptions, whereas local knowledge often employs objective and systematic methods. Moreover, individuals can hold both forms of knowledge at the same time.

Nevertheless, a strength of the final plan is its degree of engagement with indigenous people and conscious use of Maori traditions, culture, and ideas in a society where ‘Englishness’ continues to be prioritised. The plan has a strong emphasis on co-producing structures, agendas, and policies to overcome the frustration residents felt towards the local authority, and low trust and legitimacy of decisions made ‘behind closed doors’. Citizens were empowered to decide how public spaces were used in the city, with community groups reclaiming many spaces that had previously been given over to commercial use. Data held by the authority was published in an open source format for free use. Training programmes for community leaders and groups were launched, along with a time bank for volunteering.

In 2015, Germany welcomed half a million asylum seekers fleeing the war in Syria. As one of the most dynamic and prosperous cities in the country, Hamburg attracted a large proportion (79,000) of the refugees accepted into Germany that year, with more to follow in 2016. The Senate of Hamburg set up the FindingPlaces platform as a mechanism for involving residents in decisions about refugee accommodation, to mitigate against potential unrest. A Human-Computer Interaction platform was designed by MIT and HafenCity University’s Science Lab to be deployed in dozens of community meetings with 500 participants. 161 locationswere chosen by citizens to be developed into new housing units for asylum seekers.

Citizens were able to interact with a map of Hamburg where empty sites were highlighted, such as parks, sports fields, car parks, disused industrial spaces, agricultural spaces on the urban periphery, and plots of undeveloped land. Sites were assessed for viability by a technical board. 44 of the 161 sites were determined to be feasible, with 6 being developed immediately and 10 being held in reserve for future development. The platform showed how digital platforms can inform citizens of the trade-offs required in making difficult decisions. Accommodation solutions were found to house 24,000 refugees, well in excess of the project’s goal of 20,000.

A challenge the project faced was a very compressed timeframe. The process had to move fast, hampering the ability to raise public awareness. Mailouts were sent to 5.1 million people in the metropolitan area, but the organisers acknowledged more could have been done. The platform could only host 20 people at any one time owing to technical limitations. Citizens also struggled at first with using the platform. However, FindingPlaces showed that participatory planning can yield success, provided there is a clear research question, strong collaboration with locals, and effective digital design. The project built up acceptance towards refugee accommodation in the city and improved public perceptions of transparency, accountability, ownership and trust in the city’s government.

Citizen science and co-production

Citizen science is known by many different names across the world, including community science, crowdsourced science, civic science, and volunteer science. Although the terms differ, they describe the same process: public involvement in the gathering and occasionally analysis of scientific data. This makes it a form of participatory action research, where volunteers are involved in creating new knowledge and answering research questions.

Not only can this have an economic benefit for commissioning organisations, but it can also make citizens feel more engaged in their local areas, strengthening a sense of community and better anchoring the research in its specific context. This can also be a means for citizens to gain new skills. Examples of citizen science include counting wildlife, amateur astronomy, collecting air pollution data, involvement in oral history projects, and cleaning up beaches and other natural environments.

Citizen scientists can also become advocates for causes. For instance, in the context of the current Covid-19 pandemic, the University of California, San Francisco has released a smartphone app to educate citizens and help them collect data to feed into scientific research. The hope is that citizen scientists will also help educate those around them on how individuals should respond to the threat of the coronavirus.

Participants in citizen science research projects can be trained or given instructions on a protocol, so that data is of an assured quality for use in scientific research. This can be a good technique for bringing together demographics who do not frequently mix in everyday life. For example, retirees and young people are often keen volunteers in citizen science projects, which can help overcome generational divides in society. It can also help those without formal educational qualifications to take part in data collection, gain new skills and networks, and be thus empowered to contribute to decisions that affect them and perhaps move into employment using these new capabilities. Scientists and researchers of course benefit through vastly increased volumes of data for their research, along with a clear way of demonstrating impact and the community involvement of their work.

A related concept is co-production, whereby citizens work with agencies and institutions to design the services and policies that affect them, from identifying needs to testing solutions. Communities are seen as equal partners in the decision-making and policymaking process, and citizens’ lived experience is incorporated alongside the technical knowledge of experts to create rooted, locally attuned responses to issues.

Sydney has a rich ecosystem of citizen science projects run by organisations across the city. This provides citizens with a wide variety of opportunities to engage in gathering knowledge, learning new skills, meeting others, and building a personal and professional network. For instance, a major development of the Chullora Wetlands involved citizen science over the period 1991-2012, with findings contributing to new policy and unlocking the potential of the site to benefit society, while also reaping economic returns.

Scientists in the city are also using citizen science to supplement marine conservation work, sustainably developing marine sites for tourism and other uses while protecting the fragile habitat. Such public involvement increases the understanding of the sites and benefits citizens who participate through educating them about the sites and scientific research methods, learning more about their local environment, making new friends, engaging in decision-making processes in a proactive manner, and participating in activities that many define as recreational. Similarly, other ecological projects in and around the city have documented the benefits of citizen science for the scientists who initiated the research.

The Australian Museum has a Centre for Citizen Science that helps the institution develop knowledge on its own collection, alongside projects to build up image libraries of local wildlife and climate activism for future cataloguing and exhibitions. The University of Sydney also initiates a large number of citizen science projects. There are many ways for citizens in Sydney to participate in co-producing knowledge and gain new skills; the website of the Australian Citizen Science Association lists hundreds of such opportunities. Anchor institutions across a city collaborating in this way can help make public organisations truly public, with benefits for the organisations as well as citizens themselves.

‘USE-IT! Unlocking Social and Economic Innovation Together’ was a collaborative project between anchor institutions across the city to test new mechanisms to help poor citizens build resilience, enhance their employment prospects, and contribute to the identification and response to problems they face. The project trained 80 residents through an accredited training programme, which is being scaled up to a community enterprise. The project also included skills matching programme that found 200 migrants with qualifications needed by the local health service, and support for social enterprises alongside research into community assets and financing.

The project sought to co-produce knowledge and thus challenge existing power dynamics, in which vulnerable citizens are acted upon rather than in collaboration with. Participants of USE-IT! gained new skills, confidence, and made meaningful impact to the strategy and decisions of many organisations. Through empowering people to shape policies and developments in their area, the project was a working model of an intersectional response to epistemic injustice in a highly diverse part of the city. It also tested theoretical debates on co-production, with residents’ lived experience being valued alongside the technical knowledge of experts.

Through 24 commissioned research projects, community researchers on USE-IT! contributed to the knowledge gathering underpinning policy formulation for organisations across areas including poverty, migrants’ integration, health, innovation, transport, food, the arts, and issues affecting the youth and elderly people. Community researchers made contributions to the UK2070 Commission and secured a £100,000 grant to tackle childhood obesity. Birmingham is one of the most diverse cities in Europe and findings from this project can offer insight to other cities on the continent as a demographic transition is forecast to take place over the coming decades. A particular strength of USE-IT! was partnering with marginalised migrant communities and empowering them to build resilience and think about what problems they saw in their areas, as well as what solutions might be appropriate.