E-participation is a growing trend in civic engagement worldwide. A review of digital tools for engagement found that digital platforms are primarily used for three key functions: monitoring of government, institutional agenda setting, and input to decision-making. This can be done on social media or dedicated sites. Digital platforms can be used for information access and exchange, petitions and online campaigning, consultations, participatory budgeting, and voting.

However, digital engagement is not a silver bullet for mass involvement in decision-making. One core problem with digital engagement is that there are barriers to the participation of certain groups. Those of poorer backgrounds, with lower educational attainment, and members both the oldest and youngest age groups, along with people with lower interest in politics, are far less likely to use such platforms. Men are much more likely to use digital platforms for engagement than women. This means that the ‘usual suspects’ who dominate politics in the physical world – better educated and wealthier white men of middle-age and above – are disproportionately represented in digital engagement too.

Another challenge of digital platforms is that they can be disconnected from political processes, or used in an advisory capacity whereby those in power continue to control the terms of the debate and all possible outcomes. Such an approach is not truly participatory and may struggle to attract public interest. After all, time is precious, and people are not often willing to give their time to initiatives without tangible outcomes that they can influence.

Moreover, building up bespoke platforms is a major challenge for engagement. This is expensive and requires significant promotion to become more widely known. However, using existing social media is also beset with difficulties. While some organisations use this approach of going to the people where they are, rather than trying to get them to come to the organisation, platforms such as Facebook and Twitter are hotbeds of trolling, hate speech, fake accounts and spam that hinder efforts at civic engagement.

The most important conditions for successful e-participation are: embeddedness in political processes; for the role that the outputs of the e-participation will play in decision-making to be clearly defined from the start; for feedback to be given to participants about what has been done with their contributions; and an effective mobilisation and engagement strategy, with communications that are tailored toward different target groups. The two case studies that follow demonstrate what an effective digital approach towards civic engagement looks like.

Betra Ísland / Better Iceland—Crowd sourcing the constitution)

In the autumn of 2019 in the lead up to the Deliberative Meeting on the constitution, held in November, same year, we at the DCD and The Citizens Foundation instigated an online crowdsourcing forum called Betra Ísland (Better Iceland). The platform was open from September 26th to November 10th 2019 where the public could share their opinion on any constitutional-related issue.

Our Podcast interviewed Róbert Bjarnason the CEO of The Citizens Foundation about the experiment.

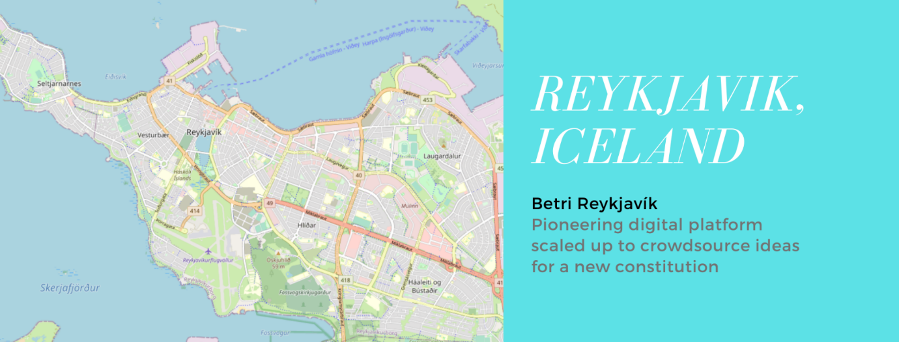

The Better Reykjavik platform has been hailed as a leading example of digital innovation in government. The platform is produced by the Citizens Foundation, working alongside Reykjavik City Council, with the aim of better integrating citizens’ voices into decisions, as well as facilitating the devolution of power and neighbourhood funding. It is one of the most successful digital platforms for engagement in the world.

A variety of projects have been operated through the platform. This includes crowdsourcing for ideas for education policy and setting the city’s democracy strategy (including young people’s issues). There have also been physical investments as a result of initiatives launched on the platform, such as new schools, community centres, cycle paths, and constructing a leisure centre in a housing estate on the urban periphery. A percentage of the city’s capital investment budget has been devolved to neighbourhoods themselves to decide how to spend it on the platform.

Better Reykjavik has proven itself to be scalable, replicable, and transferrable: key tests of digital engagement. It has recently been scaled up to the ‘Better Iceland’ platform, to crowdsource ideas for the new Constitution of Iceland. The technology has been piloted in other cities across Europe, such as Madrid and Dundee.

Reykjavik is a small city and is also highly prosperous. As a national capital, it hosts a range of institutions that give it a different dynamic to regional cities. In addition, the city is far less diverse than many in Europe, although minorities do exist, such as a relatively large Polish community. These conditions impact on the success of Better Reykjavik. Nevertheless, while the platform has an automatic translation function built in, more could be done to include migrants’ perspectives, such as a dedicated section of the platform for issues specific to migrants. In a conversation with Robert Bjarnason, head of the Citizens Foundation, he said the two keys to the platform’s success were embeddedness in the political process and constant marketing of achievements to show citizens that the platform is worth engaging with.

The synAthina platform aims to develop a participatory culture in the Greek capital, where public trust in politics was low following the financial crisis. The platform is geared towards problem identification, problem-solving, and political reform. If regulations hinder citizens from carrying out popular ideas, the synAthina team works with Athens City Council to update relevant regulations and policies.

Thousands of projects have launched on synAthina since 2013, with hundreds of civic groups organised to tackle problems in the city, from litter and graffiti to education and inclusion. The platform is a portal for posting training and internship opportunities as well as advertising cultural events in the city, encouraging people to use it in their everyday lives and build up awareness of the platform. Cultural institutions promote their schedules on synAthina and create bespoke opportunities to take part in their work through volunteering and placements. This is thus a collaboration between anchor institutions across the city.

A particular strength of the platform is how it has been used to help the city cope with the ongoing migrant crisis in Greece. Alongside the digital platform, synAthina offers a meeting space in the city centre that groups on the platform can book to use, free of charge, 24 hours a day. Support groups targeted towards marginalised citizens that have few resources benefit from this access to a safe physical space.

The successive of the project has been iterative, developing over time. The platform offers community groups space and connections with the municipality, building trust. Given the significant financial pressure on the city, citizen groups have organised to provide services. Athenians have volunteered to teach asylum seekers the Greek language, and the University of Athens has offered free courses to teach new skills to refugees, enabling them to build new lives and thus integrate into the city. Citizens’ groups and the local authority alike put out ‘open calls’ on the platform, seeking help from volunteers with time or skills to offer.